The Nazis were not just adept at betraying and deceiving the masses through language —the most critical point of Victor Klemperer’s The Language of the Third Reich—they also used signs, images, and symbols to poison their minds. Klemperer goes to great lengths to point out these tools as well in the LTI.

Much like the poverty of their language—the repetition of words, the repeated idiomatic expressions, the overuse of empty terms, nonsensical neologisms, and so on—Klemperer also states that their imagery reflected the same patterns. He writes:

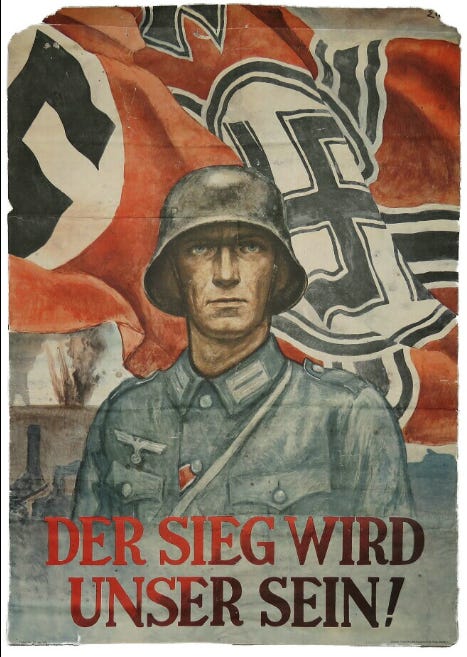

In general Nazi posters looked alike. One was invariably confronted with the same breed of brutal and doggedly erect warrior, with a flag or a rifle or a sword, in SA, SS[,] or military uniform, or alternatively naked; they always displayed military strength and fantatical Will; muscles, toughness[,] and complete absence of introspection were the characteristics of these advertisements for sport and war and obedience to the Will of the Führer. ‘We are the Führer’s serfs!’ a secondary schooler teacher declaimed with due pathos in the presence of a number of Dresden philologists shortly after Hitler took up office; ever since then the word had screamed out to me from all the posters and special issue stamps of the Third Reich; and if women were portrayed it was as the heroic Nordic wives of heroic Nordic men.1

With vacuous, blue eyes, unmoved by the explosions behind him, this poster above illustrates Klemperer’s analysis of the typical Nazi poster from the time. The embodiment of strength and fanatical Will, he tells his Volksgenossen (national comrades) that victory will be theirs! Drawing them into the struggle, the masses are reminded that the front has everything to do with them as a collective.

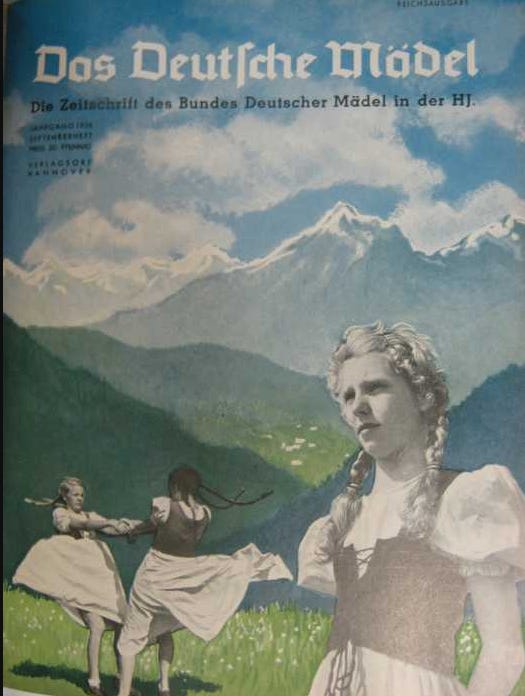

As Klemperer also points out, and to ensure gender lines are clearly delineated, German women depicted on posters are always extremely Nordic/Aryan in appearance, wearing dirndls,2 a traditional Bavarian dress, typically having braided blonde hair, and—naturally—possessing crystal blue eyes.

The poster above depicts girls, but its imagery resembles that described by Klemperer in the LTI, specifically Nordic-looking women. As for the language itself, Klemperer also focuses on the term “das Mädel.” Instead of using the more common term “Mädchen,” meaning girl or girls, the Nazis implemented “Mädel,” which translates to “lass,” a more traditional word. The same goes with boys. As Klemperer points out, instead of being called the usual “Knaben,” they are referred to as “Jungen.” The reasoning behind this, and other terminology, incorporated into imagery, as seen above, was to manipulate the collective into a kitschy, sentimental emotional state. In short, it was another means to an end, aimed at pacifying the masses.

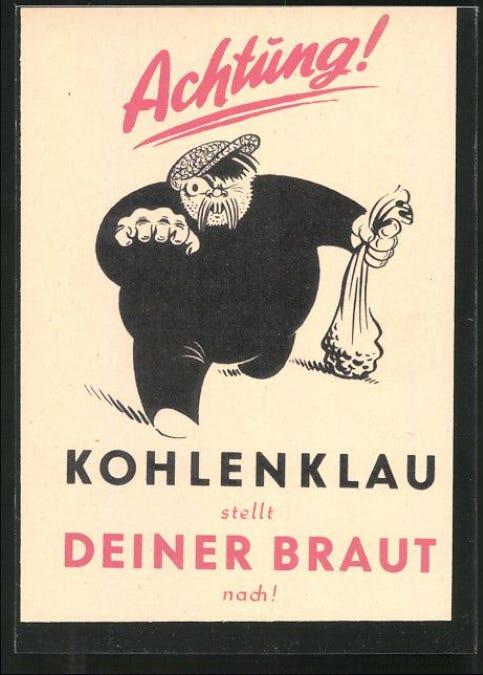

As the war efforts continued and rations became necessary, the Nazis played upon the population’s emotions even more. Insisting on sacrifice, contributing to the war effort, and using guilt as a coercive tool, Klemperer also noted these types of related images. But there’s one image in particular that stuck out to him of a distinct character who comes into play: Kohlenklau {the term literally translates as coal thief}.

While Klemperer noted that most Nazi posters had a ubiquitous appearance, he observed that this poster—Kohlenklau—was peculiar. This mischievous character symbolized the wastefulness of using coal at home, so Kohlenklau served as a warning not to waste coal and energy once the war began in order to conserve it for the frontlines and transportation needs. For example, Klemperer overheard a woman at work laughing about how a fellow worker resembled Kohlenklau, remarking how much the image of the character had become embedded in everyday language.3

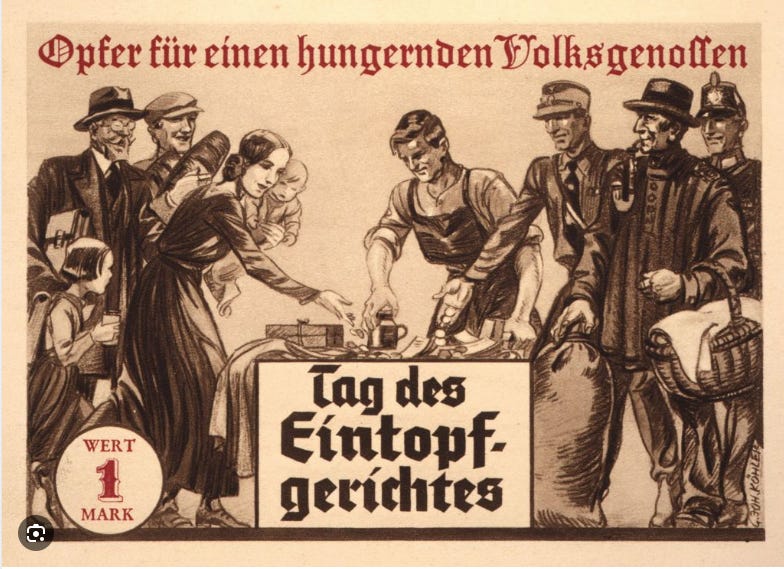

Posters not only warned of saving coal for the frontlines and helping with transportation for rail, but they also made announcements for Eintopf, which, as Klemperer notes, translates as “stew,” but is literally “single pot.” After reading in a paper “official instructions for making an “Eintopf,” which he found himself perturbed by, he explained:

What a crude and provocative technique—used initially during the First World War—to advertise some delicacy or other by arousing patriotic feelings; how clever and evocative to give food regulations a name of this kind. The same dish for everyone, a national community {Volksgemeinschaft} rooted in the most everyday and eesssential of things, a uniform simplicity for rich and poor in the service of the fatherland, the most momentous thing encapsulated in a plain and simple word! Eintopf! —all of us eat from one and the same pot…’ The word may well have been widespread for a long time as a culinary terminus technicus:4 introducing it, loaded with emotional associations, into the official language of the LTI is, from a Nazi point of view, a stroke of genius.5

Just as Klemperer points out, the Nazis are “arousing patriotic feelings” by using a technical term that is loaded with long-held culinary emotional signifiers. The Einkopf means so much more than just one pot stew to the German people, and that is precisely why Klemperer calls it a “stroke of genius,” at least to the Nazis, as they have weaponized sentimentality to rouse the public into sympathy and support of everything they are carrying out, which includes, not just the war, but genocide. These are the subtle, yet powerful ways in which they powerfully hypnotized the public into consent and complicity in crimes against humanity.6 (Germans were not innocent of the crimes against humanity being committed.)

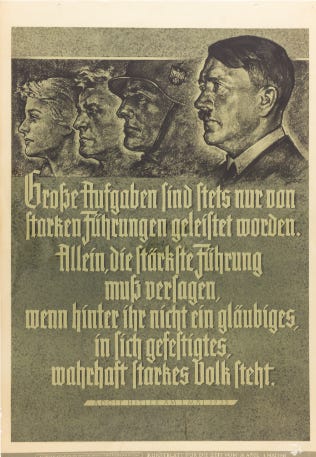

The Nazis, however, were masterful in their propaganda, as Klemperer meticulously illustrates through language and their imagery, signs, and symbols. In addition, they explicitly suggested through posters that the Führer needed the Volksgenossen, as shown in the image below.

However, it’s important to note that the people, Volk, or Volksgenossen are not an active agent in the description above. Instead, this reads as them representing a solid monolith, a “block of stone,” as Klemperer describes them, lacking all agency, personality, or individuality. In addition, and not surprisingly, the face highlighted and central is Adolf Hitler’s. The others depicted are obscured, downplayed, and not nearly as prominent. They mimic his profile, too. After all, they followed his orders, and indeed, this was another critical message that Germans had on banners, a devotional message to the Führer, something Klemperer also notes bitterly in the LTI. In fact, they apparently would paint it on their homes, as shown below.

All of this clever, insidious manipulation would lead the Volksgenossen to complicitly commit murderous acts on the battlefields {Schlachtfelden}, both on the home front and abroad.

Stay tuned for the third and final installment analyzing Victor Klemperer’s LTI. The next piece will focus on antisemitism, ableism, and more images related to the war.

Victor Klemperer, The Language of the Third Reich, trans. Martin Brady (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013), 88.

The dirndl is a relatively new form of clothing in Bavaria, Germany, as well as Austria. It only dates back to the 18th and 19th centuries.

There was even a board game created called Jagd auf Kohlenklau (Hunt for the Coal Thief) to reinforce the message of saving coal. Source: British Museum (last accessed August 31, 2025).

Latin for “technical term.”

Victor Klemperer, The Language of the Third Reich, trans. Martin Brady (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013), 250.

I should note that the term “genocide” did not yet exist. However, the Nazis and the population were fully aware that what they were doing against the Jews and other groups of people was morally and ethically wrong. (The term, however, “crimes against humanity” did. It was coined in 1915 when the Turks committed genocide against the Armenians.)

Ostensibly, there is heavy investment in national messaging- particularly during war efforts. I wonder if you have a personal take on messaging during modern warfare. Would you proffer an opinion on what Klemperer would have to say about messaging (and communications) during today's Russo-Ukraine War?

I haven't read your initial installment of This Piece, but so many questions are begging. For one, I'm wondering what constitutes "propaganda" according to someone like Klemperer; and secondly, I'm wondering whether both Russia and Ukraine engage in propaganda tactics, and whether ancillary publications (from foreign outlets) of either side's messaging constitutes agreeable definitions of propaganda.

[Don't feel obligated to answer all of This. Your Article just prompted my thinking, a bit. You wrote an intriguing piece.

And, by the way, you have quite the peculiar (to me), cool and remarkable name.]

Thank you very much for this! I've read his Diaries and this book has forever been on my to read list.