Part I: Victor Klemperer's The Language of the Third Reich

How Language Functions as a Propagandistic Tool for Tyranny and Control of the Masses

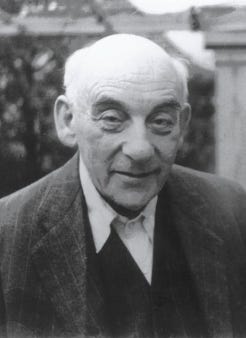

Victor Klemperer (1881 - 1960), a journalist, German philologist, memoirist, and forced laborer, found himself in a peculiar predicament when the Nazis came to power in Germany. Although Jewish by birth,1 he was married to an “Aryan” woman, Eva Schlemmer, which saved him from the fate of deportation to a concentration camp. As his rights were being stripped away — he lost the right to drive, to own pets, to go to the movies, to use the tram unless going to work, to smoke cigarettes or cigars, to buy meat, etc., etc. — he dedicated himself obsessively to his diaries, which documented the mundane to the profound.2 Once the Nazi Party firmly took over, however, Klemperer shifted his attention to public life in his writings, meticulously documented the shift in attitudes of the vox populi,3 and also paid particular attention to the political manifestations of Nazism in language.

Once he lost his library privileges and was no longer able to continue his academic research, he began to develop a theory of the Lingua Tertii Imperii, which he sardonically abbreviated as LTI,4 meaning language of the Third Reich. This project eventually became a book, which was first published in 1947 as the Lingua Tertii Imperii: Notizbuch eines Philologen (The Language of the Third Reich: A Philologist’s Notebook, or LTI).

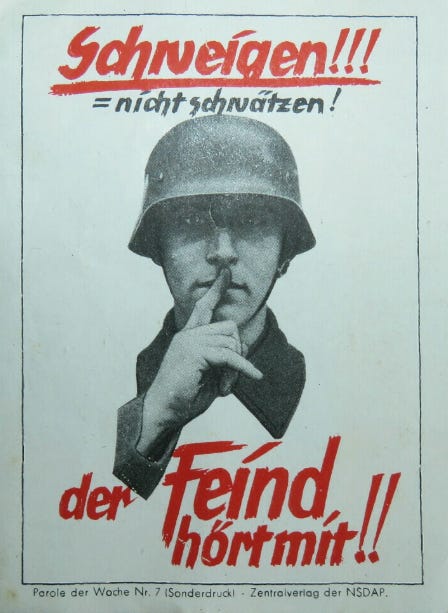

Klemperer’s philological development of LTI was all-encompassing in its usage of materials — it drew from the Volk’s everyday sayings, the leaders’ speeches on the radio,5 newspaper clippings, propaganda posters, personal conversations, literature of the day, and more. Klemperer contended that the Nazi’s language was like “arsenic,” given in repeated, tiny doses, sickening the entire population in its impoverished, repetitive simplicity. He writes, “Nazism permeated the flesh and blood of the people through single words, idioms[,] and sentence structures which were imposed on them in a million repetitions and taken on board mechanically and unconsciously.”6 This poisoning was intended to depersonalize and separate people from their identities, turning them into the masses. This “poison is everywhere,” he noted chillingly in LTI. Klemperer continues:

The sole purpose of LTI is to strip everyone of their individuality, to paralyse them as personalities, to make them unthinking and docile cattle in a herd driven and hounded in a particular direction, to turn them into atoms in a huge rolling block of stone. The LTI is a language of mass fanaticism. Where it addresses the individual — and not just his will but all his intellect — where it educates, it teaches means of breeding fanaticism and techniques of mass suggestion.7

With the loss of individuality, the notion of the private is also obliterated. As Klemperer aptly points out, “LTI no more drew a distinction between private and public spheres than it did between written and spoken language — everything remains oral and everything remains public. One of their banners contends that ‘You are nothing, your people is everything.”8 This Nazi messaging is explicit: first, your personality and individuality mean nothing. Second, even if you do have thoughts of your own, you are never alone in them. Someone is always watching, even those closest to you.9

Central to LTI is the blinding hatred of the Jew and “solving” the Jewish problem, which eventually became “The Final Solution.” Naturally, Mein Kampf served as the primary source for this ignorant, racist, murderous ire. But there are deeper roots: German Romanticism. Klemperer explains:

Nationalism Socialism is a most a poisonous consequence, more properly overconsequence, of German Romanticism; it is just as guilty or innocent of National Socialism as Christianity is of the Inquisition … it finds its strongest expression in the racial problem, and this in turn emerges most strongly in the Jewish question. Thus the Jewish question represents the ‘essential core’ and the quintessence of National Socialism. And it is precisely this kernel that demonstrates the mendacity and absolute loss of intellect, the absolute descent into the Hell of Romanticism in the Third Reich. The Jewish problem is the poison gland of the swastika viper.10

While the roots of the Nazi’s Jewish problem are based upon Romanticism, the logic of anti-semitic hatred, and the dehumanization of the Jewish people, is based on the language of (pseudo) science to appeal to the petty bourgeoisie. No longer a group of people different by practices, customs, or religion, the Jews are distinguished according to their blood {blut} and race {Rasse}. Klemperer explains:

If you base anti-Semitism on the basis of race, you don’t only give it a scientific or pseudo scientific foundation, but also a basis in traditional folk history {eine ursprünglich volkstümliche Basis} which makes it indestructible because a man can change his coat, his customs, his education[,] and his belief, but not his blood.11

Thus, der Jude as a word becomes one that saturates the language, and the adjective “jüdisch” {Jewish}12 becomes the word par excellence for the Nazis to repeat over and over again to the masses, invoking catastropic consequences for the Jewish people across Europe. Naturally, those weren’t the only terms that were used ad nauseam. Fanatisch {fanatical} and Fanatismus {Fanaticism} also inundated everyday use. These latter terms also stand out as the meaning behind them changed under Nazism, much to Klemperer’s surprise and chagrin.

Klemperer provides the reader with a brief history of the negative connotations for fanatical and fanaticism in both French and German. For example, the French Enlightenment thinkers attacked religion and religious institutions, since they were steeped in rationalism, for being fanatique {fanatical}. (He also points out that Jean-Jacques Rousseau used the term negatively.) In addition, in German, before the Third Reich, the terms were not used positively but rather in a perjorative sense. But then that changed. Klemperer observes:

the word ‘fanatical’ was, throughout the entire era of the Third Reich, an inordinately complimentary epithet. It represents an inflation of the terms ‘courageous',’ ‘devoted’ and ‘persistent;’ to be more precise, it is a gloriously eloquent fusion of all of these virtues, and even the most pejorative connotation of the word was dropped from general LTI usage. On public holidays, on Hitler’s birthday, for example, or, for example, on the anniversary of the day the Nazis came to power, there wasn’t a single newspaper article, message of congratulations, or address to some army unit or organization, which didn’t include a “fanatical vow {fanatisches Gelöbnis} or ‘fanatical declaration {fanatisches Bekenntnis},’ or which didn’t affirm its ‘fanatical belief {fanatischen Glauben} in the everlasting life of Hitler’s Reich.13

And it wasn’t just in the realm of politics that Klemperer noted this phenomenon. He heard it used in everyday life conversations and saw it in fiction, too. Even at the end of the war, he noted that the troops were “fighting fanatically!” Notably, Klemperer states that just a year after the Third Reich collapsed, the terms ceased to be used. They had all but disappeared from the vernacular, at least in terms of being used in a positive sense.

Silence was also another weapon imposed upon Germans. Words that were not used or spoken were just as important as those that were used and spoken. As the Germans were being sorely beaten in battle after battle at the end of World War II, Klemperer observes, “The fact that this movement was constantly backwards was never said in so many words, the fact was covered up with veil after veil; the words Niederlage {defeat} and Rückzug {retreat}, and above all Flucht {flight} remain unspoken.”14 The denial ran deep with the Germans, even up until to the end when Berlin was being bombed to smithereens.

Klemperer’s commentary on language during the Third Reich is prescient for our own time and should serve as cautionary advice. If one does not think for oneself, the language of fascist propaganda and those in power will do one’s thinking. As Klemperer eloquently notes, “language does not simply write and think for me, it also increasingly dictates my feelings and governs my entire spiritual being the more unquestioningly and unconsciously I abandon myself to it.”15 That should serve as a warning to us all, especially now. Choose your words wisely and think about what you’re reading and listening to, wherever or whatever that may be.

In order to obtain work in academia in Germany, Klemperer was baptized in 1912. But that did not matter to the Nazis. He was considered a Jew to them, plus his father had been a Rabbi.

Latin for “voice of the people.”

The Nazis began obsessively abbreviating terms, so Klemperer was mocking them in his diary for that practice.

Although it was illegal for Jews to listen to the radio, and punishable by death, when Klemperer worked as a forced laborer, he was able to listen to the speeches of Hitler, Goebbels, and others.

Victor Klemper, The Language of the Third Reich, trans. Martin Brady (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013), 15.

Ibid., 23.

Ibid., 23.

Ibid., 23.

Entry for September 5, 1944 in Victor Klemperer, I Will Bear Witness: A Diary of the Nazi Years, 1942–1945, trans. Martin Chalmers (New York: The Modern Library, 2001), 353.

Victor Klemper, The Language of the Third Reich, trans. Martin Brady (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013), 180.

Ibid., 181.

Victor Klemper, The Language of the Third Reich, trans. Martin Brady (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013), 62.

Ibid., 234.

Ibid., 15.

😃Excellent piece and dynamic writing! I energetically read to the end without pause and then read twice more with time In between to absorb.

The content is of particular interest to me firstly, because I am obsessed with understanding how word choice influences interpersonal communication. I have always been one to believe diction is never an accident and holds specific meaning to what people are communicating whether they thought about it beforehand or not.

More specifically, I explore the same manipulative language diction in relationship systems like families, and how it stymies the development of individual personalities.

I’m so excited because you so beautifully explained so perfectly my (not as organized) understanding along with poignant quotes from an historical figure I never would have heard of otherwise.

You’ve made it rather efficient for me to further my understanding of how interpersonal dialogue influences on individual development as well as provided further proof in my belief that our culture most definitely can and does imitate how we manage our family systems.

I could quote the whole paragraph! But I will say that “paralyze the as personalities” it absolutely brilliant. I will be “keeping” that one.

I could go on with my thoughts, but will simply say I’m grateful you warmly interacted with me on a random note in my feed I commented on.

Thank goodness that even in the darkest, most oppressive days there stands a person willing to share the truth. Without diaries and stories like these, all we would have are bodies and ruble, which even now there are those who try to ignore it or change the narrative (like January 6th was just a stroll through the Capitol or the death camps are some sort of mirage). They want us to think that our eyes are playing tricks on us when they are the actual tricksters. Thank you for bringing this remarkable man to light. I'm looking forward to more.