LONG READ - On the Urgency of Unlearning Eugenics: Dagmar Herzog's Work on the Entanglement of Sexuality, Reproductive Rights, and Disability Rights in Post-Nazi Europe

Although written in 2020, Dagmar Herzog’s Unlearning Eugenics: Sexuality, Reproduction, and Disability Rights in Post-Nazi Europe remains a timely study on the way in which reproductive rights and disability rights were dangerously and, I argue, oftentimes, cynically entangled to undermine abortion access in post-war Europe during the 1960s through the early 2000s. By attempting to limit access in Western and Eastern Europe to abortion and also pitting reproductive rights activists against disability rights activists, Herzog explains, “[t]wo traditionally progressive goals [of the movements were] thus turned against each other.”1

Starting in the mid-2000s, in many European countries, “abortion opponents . . . [began] promoting restrictions on sexual and reproductive self-determination as justice for the physically and cognitively disabled. Abortion on the grounds of fetal anomaly [became] one of the most fraught areas of bioethical and political controversy.”2 These issues, as Herzog notes, played out in public and private spaces, just as they were implementing austerity measures, meaning that those with differently abled bodies were losing the aid needed to live healthy and whole lives.3

At the crux of this debate, as Herzog notes, was the specter of the Nazis’ mass murder of the disabled that eventually culminated in the Holocaust of European Jews.4

At the heart of the problem, Herzog pointedly contends, is how Germans never came to terms with the mass murder of the disabled in Nazi Germany. In so doing, they would have to “unlearn eugenics,” something that hadn’t even crossed their minds. (This issue was apparently too bothersome to even think about.) Even worse, in Germany, disabled people were treated with disdain, and the public even embraced former Nazi doctors. Herzog explains:

In all of this, individuals with disabilities, whether physical, emotional, or cognitive, were hardly ever understood or treated as agents with personal dignity and rights. Patronizing attitudes, ranging from pity to contempt, continued to be the norm; barriers to participation in political, social, and cultural life remained ubiquitious. In Germany, West and East, individuals who had been sterilized and family members of those murdered were treated as contaminated by the shame; popular support for the perpetrator doctors was demonstratively substantial [my emphasis]. In numerous other nations —including, conspicuously, continuously democratic ones—eugenic ideas that had flourished with especial vigor in the first decades of the twentieth century persisted undisturbed by the facts of Nazism and its horrors to inform treatment of individuals with cognitive disabilities and psychiatric conditions in particular.5

In fact, it would take four decades for the disability rights movement to be recognized by the public and mainstream popular media, despite its emergence in the mid-1970s. But first, a brief history of the Nazi’s mass murder of the disabled is imperative in order to contextualize the emergent disability rights movement vis-à-vis the women’s rights/feminist movement and their concomitant reproductive rights allegiances.

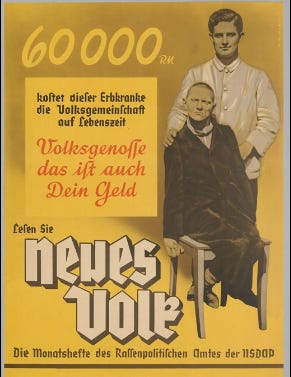

The image6 above shows a disabled individual, whom the Nazis called an Erbkranke (“hereditarily ill”) person. The term is extremely offensive and associated with the Nazis. The poster indicates that the disabled person is a burden to society, given how much he costs each citizen to purportedly “maintain his life,” which is eugenicist thinking. This ideological framing is in opposition to respect and dignity toward human life.

“Thou Shalt Not Kill” and The Peter Singer Debacle

Herzog grimly captures the historical attitude of the Nazi Party towards the disabled when quoting Eugen Stähle, a doctor and head of the Division of Health at the Württemberg Ministry of Interior, who said, “‘Thou shalt not kill. That is not divine law, that’s Jewish invention.’” Stähle was responding to Protestant leaders’ protests who had learned that they were carrying out mass murders of disabled people in a plan called Aktion 4.7 This first phase, which was intended to remain secret, was called Action Merciful Death (Aktion Gnadentod), and lasted from January 1940 to August 1941. In total, the Nazis murdered 70,273 people with carbon monoxide poisoning in “six specially designed buildings” during this phase of the killings. These buildings had formerly been used to care for people with psychiatric or cognitive disabilities, and now, in the early 1940s, they were being used for mass slaughter.

There was eventually such an uproar by religious leaders that Hitler called the killings off. However, the program resumed under a “second, decentralized phase that lasted even beyond the end of the war in May 1945.”8 A total of 290,000 people were killed by medications through overdosing, poisonings, or deliberate starvation.9 Once the staff had stopped working at what the Nazis called “T4,” with knowledge of how to use carbon monoxide gas in the chambers, they were moved to Poland to implement the mass murder of Jews of the Holocaust (these workers wound up in the death factories at Belzec, Sobibor, and Treblinka).

This genocidal history would come to thread itself through debates about reproductive rights, women’s rights, and disability rights, with ideological facets of those who wished to restrict abortion access, twisting how the past was interpreted so as to convolute how to convey it in an attempt to influence public discourse. The end goal, of course, was to change the laws on the books, with the hopes of enforcing rigid antiabortion laws, making it harder for those to have access to abortion services, if any at all.

The summer of 1989 served as a major flashpoint on this issue of disability rights and reproductive rights when Peter Singer, an Australian philosopher and an animal rights advocate, was invited to speak in Germany. A group called Life Assistance (Lebenshilfe) had invited him to Marburg to speak at a conference called “Biotechnology—Ethics—Mental Disability.” Furthermore, he had been asked to speak about a specific topic: “Do severely disabled newborn infants have a right to life?” Singer’s short answer to the question was “no.” There was so much outrage through letters and the fear of enormous protests after people learned of the recent book he had published in 1985, titled Should the Baby Live?, that Singer was only able to speak in one German town.

It just so happened that during the same summer, Ernst Klee, a well-known “nonacademic historian” and advocate for disabled people, brought up the infamous Stähle quote mentioned above. The quote was published, with other remarks by Klee, in the widely read Die Zeit, just around the time Singer was scheduled for his tour of Germany. The protestations ensued, and Singer lamented the reactions.

The results of Singer’s planned talks, plus the publication of his book, influenced international scholarship and activism within German during the 1980s and 1990s,10 forcing many “to elucidate the multiple links—in staffing, in gassing, technology, but also in the attitude toward ‘lives unworthy of life’11—between the murder of individuals with disabilities and the Holocaust of European Jewry.”12

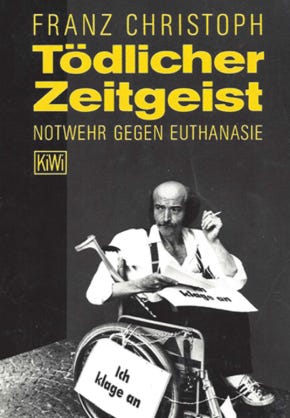

Franz Christoph, a founder of the “cripple movement” (Krüppelbewegung), had another view on these raging debates.13 As Herzog writes:

Christoph was intent on putting forward a different interpretation of how the Nazi past mattered—not, as Singer’s proponents claimed, because it caused German conversations to be out of step with international trends around assisted suicide and related matters but rather to articulate why talk could be so offensive. It was, Christoph said, ‘precisely these kinds of scholarly discussions and discourses that were precursors of what came to be, beginning fifty years ago, the determination of ‘life unworthy of life.’ The trouble was the way that the question was being established as even legitimately posable . . . A one woman in the cripple movement had phrased the point succinctly, as quoted by Christoph: ‘We cannot just tolerate it, when they talk about whether we may live or not. . . . It is an incredible intolerance, when the human dignity and personhood of disabled people is massively assaulted, when the violability of human life is therewith even more socially legitimated.14

Herzog notes that the widely circulated magazine, Der Spiegel, caught on to Christoph’s powerful statement and took a picture of him at a conference on assisted suicide where he wore a garbage bag that read “I am unworthy of life.” The photograph was accompanied by an image of the gray buses, like the one pictured above, that Nazis used for the T4 program, which included “a copy of Hitler’s order, backdated to the start of the war on Poland in September 1939.”15

As a result of this image and the hard-fought efforts of the Krüppelbewegung, the public was finally paying attention, and the tide had turned. The public had finally come to recognize the connection between the Nazis’ past and the disability activists’ demands for their voices to be heard.

Yet, the Singer debacle continued to simmer, hurting the women’s rights movement. As Singer argued, there was no difference between killing a fetus and killing a newborn child. He added, “The difference between newborns had to do with parents’ desires for them, and Singer assumed that parents desired the disabled less [my emphasis].”16 He went as far as to say, since some disabilities aren’t apparent until later, that infanticide is permissible a month after birth. Singer went further in his book, Practical Ethics, arguing, “‘I shall concentrate on infants, although everything I say about them would apply to older children or adults whose mental age remains that of an infant.’”17

Most feminists and abortion advocates apparently accepted this debate, despite reluctantly finding his argument repugnant. Antiabortion advocates seized on the opportunity and reached out to disability rights groups in an attempt to forge alliances. However, disability rights groups responded defensively. For example, while the Bremen activists took issue with abortions “on grounds of disability was a problem for them (‘we are . . . opposed to . . . the eugenic indication’), they rejected the claim to criminalize all abortions.”18 (At the time, antiabortion activists were hoping to outlaw abortion by eliminating Paragraph 218, which is the German law on abortion.)

Furthermore, this antiabortion group compared abortions to Auschwitz, which the Bremen disability group found “conspicuously tasteless,” and also added, “we find this comparison [of euthanasia at Auschwitz] to make a mockery of the victims and survivors of the concentration camps.”19

Others in the disability movement also saw how they were being used as propaganda tools by the antiabortion movement. While conservative politicians were busy cutting funding to them, they were conflating disability rights with the desire to eliminate abortion rights. At a critical rally being held at Hamadar, one of the Nazi killing centers that had previously been a psychiatric clinic, where protestors and counterprotestors showed up, the Federal Association of Disabled and Crippled Initiatives spoke there and said, “‘We cripples will not let ourselves be used as propaganda objects!’”20

The Flourishing of Disability Rights, Sexuality, and “Becoming-Disabled”

In our new century, disability rights have gained recognition in Europe and the U.S. and, as Herzog notes, “even celebration.” Herzog points to numerous campaigns in Italy, the Czech Republic, and Switzerland that promote difference and disability. In Italy, the campaign was called “E Allora?” (So?); similarly, in the Czech Republic, a group called Charita Opava ran slogans that read: “No a co?” (So what?), and in Switzerland, they had images with the inscription: “Pro infirmis. Un Handicap. Aucune limite.” (Pro infirm. A Handicap. No Limits.).

These images are natural shots of individuals living their lives fully, just like anybody else.

Pro Infirmis, as Herzog points out in her footnotes, also created a moving video, with the slogan, “Because who is perfect?,” which can be viewed below.

As shown in the video above, the clip is of several disabled people who meet with a fashion designer who recreates their bodies as mannequins who later have women clothe their recreated bodies. The disabled people then interact with their recreated (naked) mannequin bodies, touching them, hugging them, admiring them.

All these messages shared with the public that disabled bodies are joyously lived in, authentic, and possess their own beingness. As Herzog explains:

By expanding the visual-aesthetic range of what is offered to the public (perhaps best understood as a very deliberate form of queering, as bodies formerly considered nonnormative become appreciatable, indeed cherishable, and eroticably desirable) and by expanding the imaginative-emotional range in offering countless opportunities for identification with different positionalities (the heroically loving, dedicated parent, the self-determining, joyful, differently abled individual, the effective and trusted worker with the laughter-sharing circle of friends, the emulation-worthy savvy consumer, the transgressive or tender lover), the public has been encouraged to a broadened grasp of human possibility and value. This is an enormous and multifaceted collective achievement. It also remains exceedingly fragile [my emphasis].21

Indeed, as I draft this piece, while there is a liberatory push for disability rights, along with LGBTQIA+ rights, and other rights for minorities, the far right is hard at work to undo the major milestones that have been achieved. It is, as Herzog points out, the “ascent of a new kind of eugenics,” and one that continues to infect and spread across the globe with the rise and domination of autocratic leaders like Donald Trump, Viktor Orbán, Vladimir Putin, and others like them in power. With the further diffusion of technocratic capitalism globally, increased disparities of wealth, and aggressive attacks on the welfare state, issues around disability rights remain a critical matter and demand our undivided attention.

Another central theme of Herzog’s work is sexual subjecthood, something that might seem a realm that is not a state, political, or economic matter. However, it has considerable economic, state, and political components. For instance, workers’ rights in this area of disability care are critical, as they are underpaid, face long hours of work, stressful work conditions, and so forth. And when these things are lacking, in my analysis, then sexual subjecthood for the disabled suffers. In addition, sexual subjecthood is also critical when it comes to self-determination and living one’s life to the fullest extent, so economic freedom, however that is defined, is also crucial.

Herzog delves into the history of how self-determination and sexual subjecthood are interrelated, too. Furthermore, self-determination wasn’t declared until after a meeting in Stockholm in 1967 by a nongovernmental group, the International League of Societies for the Mentally Handicapped.22 Most importantly, however, in terms of sexual subjecthood, was the recognition of the sexual subjecthood of those with disabilities. As Spanish sexologist Gemme Deulofeu, who worked with an organization called Yes, We Fuck, asserted, “‘The disabled have a right to sexual joy.’”23

Sexual subjecthood may seem like something only for the bedroom, but it also bleeds into issues surrounding political rights, as Herzog aptly points out. French psychoanalyst Julia Kristeva argues that disability “creates ‘this exclusion that is not like others.’” She also blasts the French for failure to include the disabled in the “cause of justice,” mainly since the country was purportedly based upon the “rights of man.” Kristeva took this further and suggested France add to their slogan, “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity,” with “Vulnerability” to the end of it.

Kristeva’s point is this: all of us are already vulnerable. Recognizing the “universality of [this] vulnerability,” she explains, “the disabled could even help to transform the able.”24

Then there are those with PMLD (profound and multiple learning disabilities). Herzog points to Duncan Mercieca and Daniela Mercieca, who have worked with children with PMLD. Most of these children are nonverbal and lack all communication abilities. Duncan Mercieca speaks about his intense desire to be around these children, and how they make him “think again.” Herzog explains his sentiments:

Invoking the standard notion that ‘success is indentified with saving time,’ therefore, ‘thinking has a fatal flaw of making us waste time,’ Merieca notes that ‘to think again, then, will be to waste time twice over,’ but he thinks this thinking-again that the children provoke in him is thus not just ‘wasting time’ but ‘time well wasted.’25

Time well wasted with children who allow Mercieca to slow down, to think again, to ponder more things in life. That’s what the children with PMLD have enabled him to do. This also allows all of us to consider the moment of “becoming-disabled” but in the joyous sense, that sense of moving to the other side of beinginess, of experiencing desire too in a celebratory way, and of universalizing26 the notion of disability in all of its fullness.27

Dagmar Herzog, Unlearning Eugenics: Sexuality, Reproduction, and Disability Rights in Post-Nazi Europe (Madison: University of Wisconsin, 2020), 3.

Ibid., 3.

Idib., 3.

Ibid., 3.

Ibid., 4.

Calisphere: University of California. UC Berkeley, Bancroft Library. German poster and broadside collection, chiefly from the Nazi party during the Second World War. Last accessed September 5, 2025. https://calisphere.org/item/ark:/28722/bk0007t7j4k/

Dagmar Herzog, Unlearning Eugenics: Sexuality, Reproduction, and Disability Rights in Post-Nazi Europe (Madison: University of Wisconsin, 2020), 44.

Ibid., 45.

Ibid., 45.

Ibid., 50.

The infamous, sadistic term in German is Lebensunwertes Leben.

Dagmar Herzog, Unlearning Eugenics: Sexuality, Reproduction, and Disability Rights in Post-Nazi Europe (Madison: University of Wisconsin, 2020), 50.

The Krüppelbewegung began in the 1970s.

Dagmar Herzog, Unlearning Eugenics: Sexuality, Reproduction, and Disability Rights in Post-Nazi Europe (Madison: University of Wisconsin, 2020), 57.

Ibid., 58.

Ibid., 59.

Ibid., 59

Ibid., 60.

Ibid., 60.

Ibid., 60.

Ibid., 71.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted in 1948, did not mention people with disabilities.

Dagmar Herzog, Unlearning Eugenics: Sexuality, Reproduction, and Disability Rights in Post-Nazi Europe (Madison: University of Wisconsin, 2020), 79.

Ibid., 83.

Ibid., 96.

Herzog delves into the notion of “universalizing” versus “minoritizing” disability, a concept derived from Queer Theory. Still, I could not address this due to the space restrictions of this essay.

That isn’t to say that disabled people are here to “show” us the way. They are humans living their lives just like we do.

Thank you for writing this important essay.

Compelling