The Substack Bubble: Why It's A Lie & Why That Bubble Will Burst

This piece originally appeared on Thistle and Moss here.

The Deception Mechanism

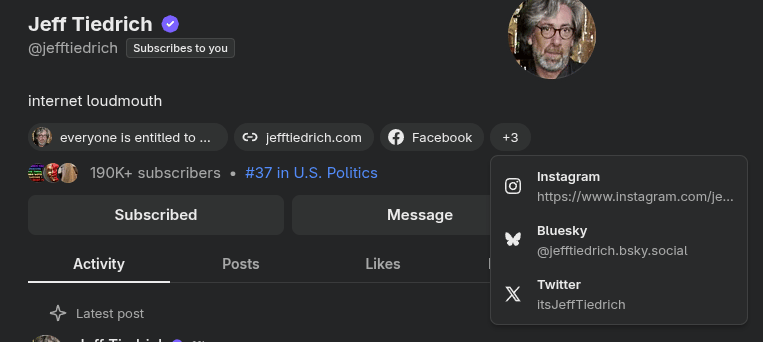

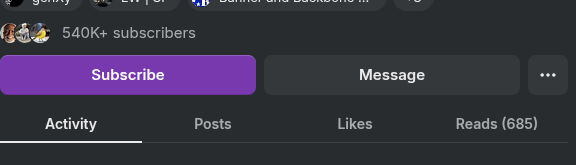

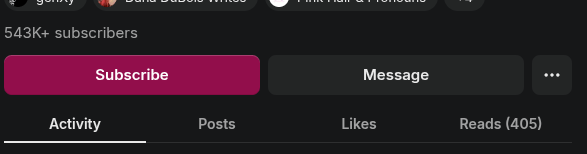

Picture this: You’re scrolling through Substack, researching political commentators, and you land on Larry’s profile. The numbers hit you like a spotlight—540,000+ subscribers. Your brain immediately calculates credibility. Half a million people trust this voice. This person has built something. This is authority incarnate, influence made flesh, a media empire in miniature.

Except it’s a lie. Not technically, perhaps, but functionally—viscerally—morally. Six months ago, Larry had approximately 2,000 subscribers. His own audience. People who chose him. Then he became a contributor to Blue Amp Media, a progressive political publication with over 540,000 subscribers. And suddenly, his profile metamorphosed. The number beside his name exploded from 2,000 to 540,000—a 270x increase that had nothing to do with his writing, his audience building, or his worth as a creator.

The subscribers didn’t move. They didn’t choose him. They chose Blue Amp Media. But Substack’s platform architecture displays Blue Amp’s subscriber count on Winnerman’s individual profile as if those hundreds of thousands of people subscribed to him. They didn’t. They can’t even see his individual posts unless Blue Amp publishes them. He doesn’t own those email addresses. He can’t export that list. If he leaves Blue Amp tomorrow, those 540,000 subscribers don’t follow him—they stay with Blue Amp, and his profile reverts to whatever meager audience he’s actually cultivated independently.

This is cosmetic credibility. Borrowed authority. Statistical catfishing on an industrial scale.

The Architecture of Deception

Substack’s contributor system operates with a peculiar sleight of hand that transforms individual writers into apparent media moguls overnight. Here’s the mechanical reality of how this works:

When someone becomes a “public contributor” to a Substack publication, their profile begins displaying what appears to be a personal subscriber count. But this number isn’t their individual subscriber count—it’s the publication’s subscriber count. The platform makes no clear distinction. There’s no asterisk, no fine print saying “subscribers to publications I contribute to, not subscribers to me personally.” The number sits there beside their name like a badge of honor they never earned.

Cliff Schecter, founder of Blue Amp Media, shows 532K+ subscribers on his profile. A recently added person, LW, a contributor: 540K+. David Shuster, another contributor: presumably similar numbers. These aren’t three separate half-million-person audiences who independently chose these three individuals. These are the same 540,000 people who subscribed to Blue Amp Media as an entity. The publication. Not the contributors.

The documentation confirms what common sense already knows: contributors have no access to subscriber data, cannot see subscription statistics, cannot export email lists, and do not retain subscribers when they leave a publication. Substack’s own help articles state explicitly that when contributors depart, “subscribers remain with the publication.” The relationship—the actual, functional, monetizable relationship—exists between the subscriber and the publication, not between the subscriber and the individual contributor.

Yet the profile display suggests otherwise. It performs otherwise. It manufactures otherwise.

Why This Constitutes Fraud

The legal definition of fraud typically requires several elements: a false representation of material fact, knowledge that the representation is false, intent to deceive, justifiable reliance by the victim, and resulting injury. While Substack’s subscriber display might technically skirt legal fraud (through the gossamer-thin technicality that these numbers are real subscriber counts—just not belonging to the individual whose profile displays them), it absolutely constitutes fraud in the colloquial, functional, ethical sense.

Material misrepresentation: The subscriber count displayed on a profile is presented as that person’s subscriber count. Contextual cues—its placement next to their name, its singular presentation, its formatting identical to genuine individual subscriber counts—all communicate “this person has this many subscribers.” But they don’t. The audience belongs to someone else.

Intent and knowledge: Substack’s product designers know exactly what they’re doing. They understand that large numbers convey authority, credibility, and social proof. They know that potential subscribers evaluate creators based on subscriber counts. They know that brands, media outlets, and other platforms use these numbers to assess who’s worth interviewing, partnering with, or promoting. They designed this system knowing that conflating publication subscriber counts with individual contributor profiles would inflate the apparent size and success of contributors.

Justifiable reliance: When someone sees “540K+ subscribers” on Larry’s profile, they’re justified in believing that Larry has 540,000 subscribers. That’s what the interface says. There’s no disclaimer. No clarification. The platform offers no way to distinguish between a person with 540,000 individual subscribers and a person displaying the subscriber count of a publication they contribute to.

Resulting harm: The harms multiply like fractals. Individual creators competing in the same space look illegitimate by comparison. How do you compete with someone showing 540,000 subscribers when you have 5,000—even if your 5,000 is real and their 540,000 is borrowed? Brands and media companies make decisions about who to work with based on these inflated numbers, directing resources toward people who haven’t actually built the audiences they appear to command. The creators themselves benefit from unearned credibility, landing speaking gigs, media appearances, book deals, and partnership opportunities based on metrics that are functionally fabricated.

The Ecosystem of Deception

This isn’t an isolated glitch. It’s part of Substack’s broader architecture of misleading growth metrics, a constellation of design choices that consistently inflate apparent audience size while obscuring actual reader engagement and creator influence. The contributor subscriber display sits at the apex of a pyramid of statistical manipulation, each layer reinforcing the others to create an environment where numbers increasingly detach from reality.

Consider the “follower versus subscriber” confusion Substack has deliberately cultivated. “Followers” on Substack can see your Notes (Substack’s Twitter-clone feature) and some reading activity, but they don’t receive your posts via email. They’re not subscribers. They’re not part of your monetizable audience. But Substack counts them. Displays them. Makes them visible. And crucially, makes them conflatable with actual subscribers in the minds of casual observers.

This linguistic sleight-of-hand—using “subscribers” and “followers” as if they’re comparable metrics when they represent wildly different relationships—creates a fog of numerical ambiguity. When someone says, “I have 50,000 on Substack,” what does that mean? Subscribers? Followers? Some combination? Are those email subscribers who receive every post, or Notes followers who see content algorithmically if they happen to scroll past? The platform benefits from this ambiguity because it allows every creator to present themselves in the most favorable numerical light.

The platform also employs pre-checked recommendation boxes—dark patterns that artificially inflate follow counts by making users opt-out rather than opt-in. When someone subscribes to one publication, Substack suggests others, with the follow/subscribe action pre-selected. Users who don’t notice or don’t care end up “following” dozens of creators they never intended to follow. Those creators see their follower counts rise and assume they’re building an audience. They’re not. They’re accumulating accidental, low-intent follows that will never convert to actual readership.

These auto-follows create ghost audiences—numbers that exist in databases but represent no genuine reader relationship, no real attention, no actual value. Yet they inflate the metrics creators see, making them feel successful, making the platform look vibrant, making the whole ecosystem appear more engaged than it actually is. It’s the digital equivalent of a store hiring actors to pretend to shop, creating the appearance of popularity to attract real customers.

Then there’s the proven “network attribution lie”—research by Elan Ullendorff demonstrating that 84% of subscribers Substack claimed came from its internal network actually originated from other sources. Substack was taking credit for audience growth it didn’t create, inflating its value proposition to creators by pretending its ecosystem delivered subscribers when external marketing actually did the work.

Think about what this means: Substack tells creators, “join our platform, benefit from network effects, our ecosystem will help you grow.” But when researchers actually tracked where subscribers came from, they found that the vast majority came from sources external to Substack—the creator’s own social media marketing, guest appearances on podcasts, mentions in other publications, word-of-mouth referrals. Substack was just the infrastructure, not the growth engine. Yet they claimed credit for growth they didn’t generate, making their platform seem more valuable than it was.

This creates a comprehensive deception ecosystem. Subscriber counts are inflated by counting publication subscribers as contributor subscribers. Follower counts are inflated by auto-follow dark patterns. Growth attribution is inflated by claiming credit for external traffic. And throughout, the platform’s interface makes these inflated numbers prominent, visible, impossible to miss—while burying or obscuring the more accurate, more modest reality beneath.

The contributor subscriber display fits seamlessly into this pattern. It’s another layer of statistical inflation, another mechanism by which Substack makes its platform—and the creators on it—appear more successful than they actually are. Each deceptive element reinforces the others. The auto-follows make follower counts look impressive. The false attribution makes growth look platform-driven. The contributor subscriber display makes individual creators look like they’ve built massive audiences. Together, they create a reality distortion field where every metric trends upward and apparent success bears less and less relationship to genuine audience connection.

The Psychological Exploitation

What makes this particularly insidious is how it exploits fundamental cognitive biases and social proof mechanisms. Humans are deeply tribal. We look for signals of who’s worth listening to, who’s legitimate, who’s been vetted by the crowd. Subscriber counts function as shorthand for credibility. “Half a million people can’t be wrong” our pattern-recognition software whispers.

When you see someone with 540,000 subscribers, you don’t just think “this person has an audience.” You think:

This person has built something significant

This person has been chosen by hundreds of thousands of individuals

This person must be worth reading if this many people actively sought them out

This person has influence—they can move half a million people

This person probably makes serious money, suggesting their work has market value

This person is established in their field

All of those assumptions are wrong when the subscriber count is borrowed. But your brain doesn’t know that. The interface doesn’t tell you. You’re left making decisions—whether to subscribe, whether to share, whether to cite this person’s work—based on a credibility signal that’s fundamentally fraudulent.

This is especially damaging for emerging creators. If you’re building an audience from scratch, competing against someone who appears to have 540,000 subscribers creates a psychological barrier that’s almost insurmountable. Why would someone subscribe to you when they can subscribe to someone with proven massive reach? Except that “proven massive reach” is a mirage. The person with 540,000 displayed subscribers might have less actual direct reach than you do. But the platform’s design ensures you’ll never know that, and potential subscribers will never know that.

The Commercial Implications

The commercial consequences of this deception extend far beyond hurt feelings and unfair competition. They distort entire markets, redirect capital flows, and create a shadow economy built on borrowed legitimacy where the numbers on screens bear increasingly tenuous relationships to the value beneath them.

Brand partnerships and sponsorships: Companies deciding who to sponsor look at subscriber counts. If LW approaches a brand with his Substack profile showing 540,000 subscribers, that brand might offer him a sponsorship deal sized for a half-million-person audience. But he can’t deliver that. He can deliver whatever exposure Blue Amp Media gives him by including his work in their publication. If Blue Amp publishes his piece, 540,000 people see it. If they don’t, essentially nobody does. He doesn’t have independent access to that audience. The brand is paying for reach he doesn’t control and might not actually deliver.

Consider the mathematics of this fraud. A brand might pay $10,000-$50,000 for a sponsored post reaching 540,000 engaged subscribers—standard industry rates for that scale. But if the contributor’s actual independent reach is 2,000 people, the cost-per-thousand (CPM) isn’t $18-$92 as the brand calculated; it’s $5,000-$25,000. The brand isn’t getting what it paid for. It’s experiencing fraud by proxy, mediated through Substack’s cosmetic credibility system.

And the contributor can’t even guarantee delivery. They don’t control the publication’s editorial calendar. Blue Amp Media might decide not to run the sponsored content. Or run it weeks late. Or edit it heavily. The contributor has presented themselves as someone who can deliver half a million impressions on demand, but they’re actually just someone who might be able to convince their editor to include sponsored content in a publication they don’t control.

Speaking engagements and media appearances: Conference organizers, podcasters, and media bookers evaluate potential guests partly by audience size. Someone with 540,000 subscribers is a more attractive booking than someone with 2,000 because they’ll theoretically bring a larger audience to the conversation. But again, that audience doesn’t belong to the contributor. They can’t mobilize those people. They can’t tell their “subscribers” to watch an interview or attend an event because those aren’t their subscribers—they’re Blue Amp Media’s subscribers.

Picture a conference organizer choosing between two speakers for a coveted keynote slot. Speaker A has 8,000 genuine individual subscribers who open their emails religiously, engage deeply with their work, and would absolutely show up or tune in if their favorite writer asked. Speaker B shows 540,000 subscribers on their Substack profile—but those are borrowed from a publication they contribute to, an audience they can’t actually mobilize or speak for.

The conference organizer chooses Speaker B. Why wouldn’t they? The numbers seem clear. But when Speaker B’s appearance doesn’t drive ticket sales or viewership, when they can’t get Blue Amp Media’s 540,000 subscribers to care about this conference they’re speaking at, the organizer feels cheated. They booked someone based on apparent reach that turned out to be a mirage. Meanwhile, Speaker A—who could have actually delivered audience engagement—got passed over because their legitimate 8,000 subscribers looked tiny next to Speaker B’s borrowed 540,000.

This pattern repeats across the media ecosystem. Podcast hosts choosing guests. Cable news bookers deciding who gets airtime. Event organizers selecting panelists. All making decisions based on subscriber counts that don’t represent what they appear to represent.

Hiring and career opportunities: Media organizations and political campaigns hire based partly on demonstrated audience-building ability. A profile showing 540,000 subscribers signals “this person knows how to connect with audiences at scale.” But if those subscribers were never built by the individual, never chosen the individual, and won’t follow the individual to a new platform, then that signal is meaningless. The person hasn’t demonstrated mass audience-building ability—they’ve demonstrated the ability to get hired as a contributor to a publication that built a mass audience.

This creates particularly pernicious dynamics in journalism and political communications hiring. A political campaign might hire a “digital strategist” showing 540,000 Substack subscribers, expecting that person to bring audience-building expertise and potentially even mobilize their subscriber base for campaign communications. But when that person arrives and can’t replicate their apparent success because it was never theirs to begin with, the campaign has wasted crucial time and resources on a hire based on fraudulent credentials.

The résumé effect amplifies the deception. “Reached 540,000+ subscribers on Substack” looks impressive in a bullet point. It suggests audience building at scale, email marketing expertise, content strategy that works. But if those subscribers were accumulated through association with a publication rather than independent audience cultivation, the résumé entry is fundamentally dishonest—even if technically accurate.

Investment and creator funding: Venture capital, creator funds, and investment dollars flow toward creators who demonstrate traction. Subscriber counts are a primary traction metric. Inflated counts attract capital that should go to creators who’ve actually built genuine audiences. This misallocates resources in the creator economy, rewarding cosmetic success over actual audience relationship building.

The creator economy has exploded into a multi-billion-dollar investment category. Funds, angel investors, and platforms themselves allocate capital to creators showing momentum. A creator pitching a media company or seeking venture funding presents their metrics: subscriber count, growth rate, engagement. If their Substack profile shows 540,000 subscribers, investors see someone who’s already achieved product-market fit, who’s proven they can build and retain an audience.

But if those 540,000 subscribers are borrowed—if they represent a publication’s audience rather than the individual’s—then the investment thesis collapses. The creator hasn’t proven they can build an audience from scratch. They’ve proven they can get hired by someone who already built an audience. Those are radically different value propositions. One suggests independent viability and growth potential. The other suggests dependence on someone else’s platform and audience.

Capital misallocated to creators with borrowed credibility is capital that doesn’t flow to creators with genuine traction. Every dollar invested based on inflated metrics is a dollar that doesn’t reach creators who’ve actually demonstrated audience-building ability. This distorts the entire creator economy, subsidizing cosmetic success while starving genuine achievement.

The Silencing Effect on Genuine Creators

Perhaps the most corrosive effect of Substack’s contributor subscriber display fraud is how it silences and demoralizes genuine independent creators.

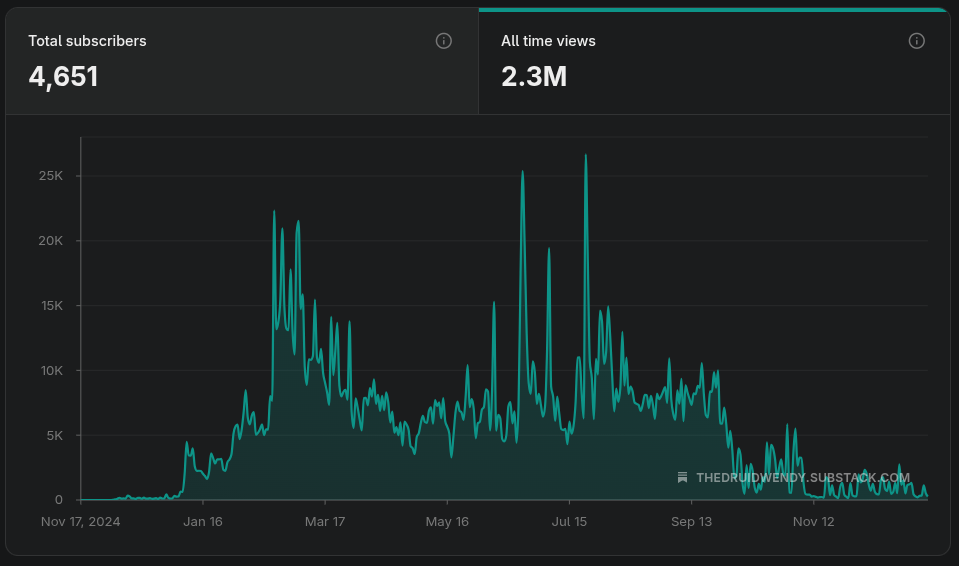

Imagine you’ve spent three years building a Substack newsletter from zero to 8,000 subscribers. Eight thousand real people who chose you, who open your emails, who engage with your work. You’ve done this through consistent quality, word-of-mouth, social media marketing, guest posts, podcast appearances—genuine audience building, one person at a time.

Then you look at your competitors in your niche and see someone with 540,000 subscribers. Your brain does the math instantly: they have 67 times your audience. You’re not even playing in the same league. Why bother? Why would anyone choose your newsletter when they could get similar content from someone with 67 times the reach?

Except they don’t have 67 times your reach. They might have less. Those 540,000 subscribers aren’t their subscribers—they’re borrowed from a publication they write for. Their actual independent subscriber count might be 2,000. You have four times their genuine audience. But you’d never know it. The platform obscures this reality, making you feel small and them feel big, based on a number that’s essentially fictional in terms of representing their actual audience-building achievement.

This dynamic suppresses competition, discourages new entrants, and creates artificial barriers to entry in what should be a relatively level playing field. Substack markets itself as democratizing media, giving individual writers direct access to audiences without institutional gatekeepers. But by allowing contributors to display publication subscriber counts as if they were personal subscriber counts, Substack creates a new form of gatekeeping—one based on cosmetic numbers rather than actual audience relationships.

The Defense: “It’s All Technically True”

Substack would likely defend this practice by arguing that everything displayed is technically accurate. These contributors are associated with a publication that has 540,000 subscribers. The numbers aren’t fabricated. No one is lying in an explicit sense.

This defense is bullshit.

Yes, the numbers are technically real. But their presentation is deliberately misleading. Context matters. Placement matters. The absence of clarifying information matters. When you display a subscriber count directly on an individual’s profile, in the exact same format and location as genuine individual subscriber counts, without any indication that this number represents something different, you’re lying through design even if you’re telling the truth through data.

It’s the statistical equivalent of someone introducing themselves by saying “I’m associated with a company that has $50 million in revenue” and letting people assume they personally generate or control that revenue. Technically true. Functionally deceptive. The intent is clear: to borrow credibility and authority from an entity you’re connected to by making it appear that authority belongs to you personally.

Substack knows this. They have entire teams of product designers and user experience professionals who understand exactly how users interpret interface elements. They know that people will see “540K+ subscribers” on Larry’s profile and think “Larry has 540,000 subscribers.” They designed it that way. They maintain it that way. The “it’s technically accurate” defense doesn’t absolve them—it indicts them for deliberately engineering deception through interface design.

Conclusion: The Cost of Borrowed Credibility

The Substack contributor subscriber display practice isn’t just misleading—it’s corrosive to the entire creator economy ecosystem the platform claims to support. It rewards affiliation over audience building. It prioritizes cosmetic metrics over genuine relationships. It creates false hierarchies based on borrowed credibility rather than actual influence.

When Lawrence Winnerman’s profile jumped from 2,000 to 540,000 subscribers because he joined Blue Amp Media as a contributor, nothing real changed about his audience, his reach, or his ability to move readers. The only thing that changed was a number on a screen—a number that would make brands, bookers, readers, and competitors treat him differently despite the underlying reality remaining identical.

That number is a lie. Not in the narrow technical sense—those 540,000 subscribers exist. But in every meaningful sense: they’re not his subscribers. They didn’t choose him. They can’t be mobilized by him. They won’t follow him if he leaves. They represent an audience he doesn’t own, didn’t build, and can’t leverage independently.

The visceral reality of this deception hits hardest when you consider the individual stories behind the numbers. Somewhere, right now, there’s a creator who spent four years building a newsletter from zero to 12,000 genuine subscribers. Every one of those 12,000 people made an active choice. They read a post, found value, entered their email address, confirmed their subscription, and continued opening emails over weeks and months and years. That creator nurtured those relationships, responded to comments, adjusted content based on feedback, showed up consistently. They earned those 12,000 subscribers through craft and commitment.

That same creator looks at competitors in their space and sees profiles displaying 500,000+ subscribers. They feel small. Inadequate. Like they’re failing at something others have mastered. They consider quitting. Why keep grinding when others have figured out how to reach 40 times as many people?

Except those others haven’t figured anything out. They just got hired by a publication that had already built a large audience. They’re wearing someone else’s numbers like a borrowed suit, looking impressive at the party while owning nothing underneath. And the creator with 12,000 genuine subscribers—who built every single relationship from scratch, who owns every email address, who could take that audience anywhere—feels like a failure because Substack’s interface made fraud look like success.

That’s the real cost. Not just the brands getting defrauded or the misallocated capital. It’s the talented creators who give up because they’re competing in what appears to be a rigged game. It’s the audiences who subscribe to people based on apparent authority that doesn’t exist. It’s the erosion of trust in metrics, in platforms, in the very idea that numbers can tell us something true about quality and connection and value.

Substack designed their platform to display this lie prominently. They maintain this system despite its obvious potential for deception. They benefit from the inflated appearance of success it creates. They’ve built an architecture that allows contributors to masquerade as media empires, to harvest credibility from associations, to perform reach they don’t possess.

And in doing so, they’ve created a system where the numbers don’t mean what they appear to mean, where credibility can be borrowed rather than earned, where the basic metrics we use to evaluate creator success have been rendered unreliable and deliberately misleading.

That’s fraud. Maybe not legally actionable fraud, but fraud in spirit, fraud in function, fraud in impact. It’s the infrastructure of deception dressed up as creator empowerment, statistical catfishing branded as democratic media.

And it’s happening right now, on thousands of profiles, distorting markets, silencing genuine creators, and replacing earned authority with cosmetic credibility that vanishes the moment the contributor walks away from the publication whose numbers they were never entitled to wear as their own.

The growth is fake. The lie is real. And Substack knows it.

After five months of struggling to trying to even set up my profile and start writing, I have thrown up my hands in frustration and despair. I just restack articles I find of importance great interest, and excellent writing.

Cryn Johansson, I did accidentally come across your writing and you have to be among the BEST on Substack. True content with value worth reading.

I have seen the mistakes I have made by subscribing to and paying for content I have no interest in. I re- evaluate each month. I now see I should be paying for all of your content by February and drop someone who is not delivering...

This article is exceptional and could not explain how substack shifts the statistics any clearer.

I clicked because I thought you meant something like “filter bubble”. But that’s another issue completely. Still, thanks. An informative post, and good stuff to know.

Then there’s someone like me, who has really invested NOTHING in substack (at least my own acct), but still has a silly number of “followers” - most of them what I call “honey trap bots” (“honeybots”?): profiles with pics of young women with big boobs and no real content. Plus a few subscribers to a “test bed” newsletter that has never really published. (Maybe I should make it real, someday.)

Lol. This mod-er-un world is a strange place.